AI-cologies for everyone

What is an AI-cology, why does it matter, and what is it good for? AI-cologies are a way of thinking about, locating, and questioning the ecologies around and in a particular AI-involving system. This essay takes the example of one specific camera to explain how AI-cologies are constructed.

Acronyms and bad puns: along with colons, these are the bedrock of the way academics name things. Today, I want to highlight a concept with a bad pun for a name. That concept is the AI-cology, an ecological understanding of AI-based technologies.

First, bear with me. We’re working with a definition of ecology that doesn’t necessarily have to be about nature or the preservation of the environment. In this case, “ecology” is a term in fairly frequent use in the social sciences to mean a holistic or systemic understanding of all the elements interacting together to make a particular situation or thing happen. You could also call it a relational view of things. The things we study, whether they’re physical objects like a power drill or digital objects like a piece of software, are made up of relations, both to other things and to other systems.

Drill-cology (an admittedly worse portmanteau)

Let’s take the power drill. Not only does the power drill require things beyond itself in the here and now to function – drill bits, for example, or a power supply – but it also has a lot of other things baked into its ability to exist. The power drill has a transnational existence, designed, perhaps, or commissioned by a company in one country, likely made in another, of elements coming from yet more sources. Its construction relies on international standards and agreements, and its use relies on yet more knowledge, skill, and movement. The ecology of the power drill is in all of the elements surrounding it, its construction, its transportation to its user, its use and yes, its eventual disposal. The elements, both material (metal, for example) and non-material (tariffs, maybe, or compatibility with the metric or imperial system of measurement), form the power drill’s ecology. The power drill is an item you can touch, but its existence and use are dependent on a whole collection of things that, at first glance, seem to be outside of the drill.

AI-cologies

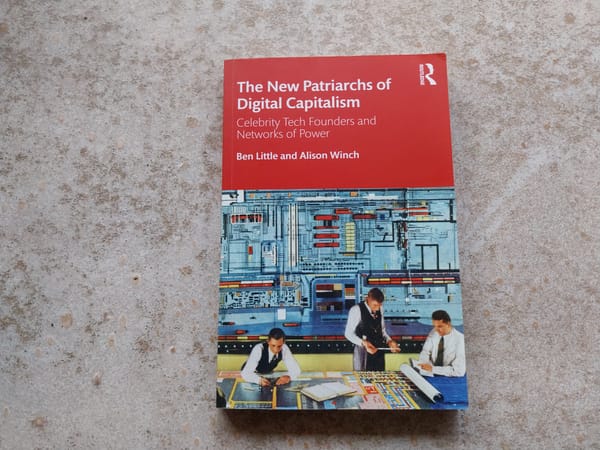

So what does that have to do with the terrible pun in this post’s title? What, in short, is an AI-cology? AI-cologies are a concept defined in Jacobs, van Houdt, and coons (2024), meant as a way of exploding the object-ness of AI. What I mean here by “object-ness” is the mystification and opacity that’s often employed in conversations about AI-based or AI-including systems. We’ve all seen it by now: AI will replace human workers; AI will change the way we think; let’s become an AI-first company; the AI said this was true. These statements treat “AI” as a discrete thing which has the power and agency to make all kinds of social change. On a more modest level, a local government might say “We want to use AI to make the beach safer.” In that conversation, the use of the term “AI” could be standing in for all kinds of different technologies which broadly fall under the AI umbrella. But the term AI, when used in that context, doesn’t mean a lot, either from a technical perspective, or from perspectives which could matter to the people who might visit the “safer” beach. That’s where AI-cologies come in.

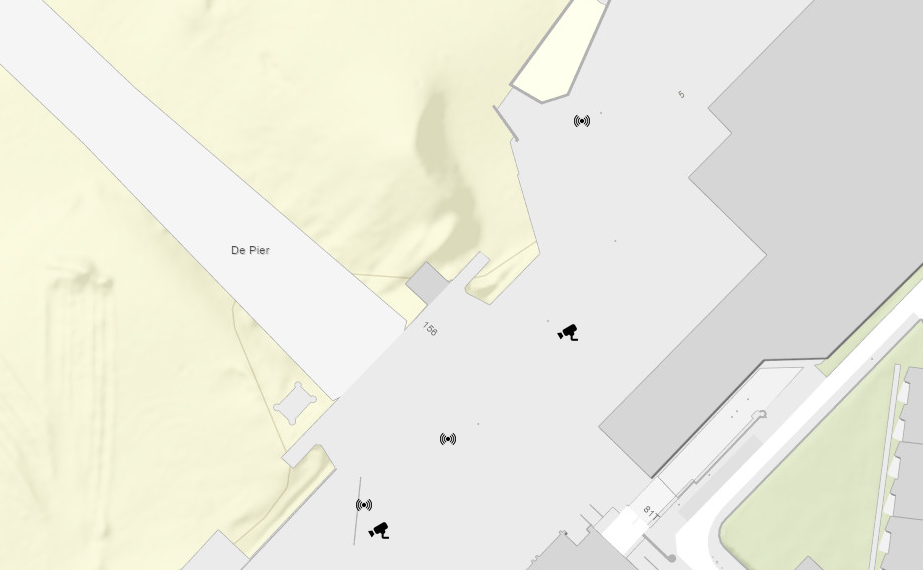

AI-cologies are a way of thinking about, locating, and questioning the ecologies around and in a particular AI-involving system. I know that sounds a bit obtuse, so let’s be practical. Let’s say we have a crowd-counting camera. That’s not specific enough. Let’s say we have a crowd-counting camera on a pole, on the boulevard at the beach in Scheveningen (a popular beach in The Hague – it has a pier). This camera, in fact: https://smartcity.denhaag.nl/use-cases/druktemetingen/. Of course, it would be better to be really specific and not just point at documentation about the camera. I can bust out the map of sensing devices the municipality has running in public space and point to the camera on that. Here it is, the little camera icon on the right, on its own (the other camera you see is hanging out next to a smart garbage can, on which more in another post):

But the best thing would be to stand under it, point up at it, and be able to say “this camera.”

The AI-cology of this one crowd-counting camera

So we have this camera, and we want to understand it. We want to understand how it works, sure, but that turns out to be a much bigger question than “How does the camera hardware fit together with the software?” which we might take as a conventional meaning of “work” for something like a camera. The question of how the camera works also includes how the camera got here, why this particular camera is in this particular place, in this particular city. “How does this camera work?” is a political question, a legal question, an ethical question, a material question, a social question, an organizational question, and so on. The working of the camera, in this case, ties into European and Dutch law, and into ethics assessment methods used before the implementation of a technology. The camera is also tied into public consultations, procurement procedures, experiments, and all kinds of other processes by which the municipality in this story does its work.

The AI-cology is not just all of the things that make it possible for the camera to be where it is and functioning in a certain way. The AI-cology is also the relationship between all of those things. So far, so good. We have a definition. An AI-cology, aside from being a terrible pun, is the ecology of an AI-using system. An AI-cology is an understanding not just of how things are right now, but also how they came to be that way. Easy.

The particular camera we’re looking at is related to a lot of different material and non-material things. It’s mounted on a pole, which seems trivial and obvious for a camera, but is still an interesting fact of its presence. The pole (and indeed, the camera itself) needs to stand up to the brutally salty and sandy wind of a beach on the edge of the North Sea. So there’s our first relation to nature. The camera requires power, and indeed, the camera’s value as crowd-counting but not image-transmitting means that power is required not just to capture images, but also to perform analysis on the images (this is computation that’s getting counted as AI in the system and indeed in the governmental algorithm register, here). Aside from power, the camera needs a network connection to transmit its numbers back to a centralized dashboard.

Values in the AI-cology

These are the very basics of the AI-cology of this particular camera. We can also focus more on the non-tangible things and look at the attitudes and laws that make it valuable to have a more privacy-respecting way of counting the crowd. We could look at public safety incidents which cause residents, local businesspeople, visitors, politicians, or civil servants to think that there should be more fine-grained crowd monitoring happening at this particular seaside area. We might then decide to start mapping out some of these things, both material and non-tangible, for the AI-cology of our camera. We can arrive at new connections by asking questions about the camera. These questions can be technical or infrastructural, they can be about context, but they can also be about the ethical, legal, and social aspects of the camera’s AI-cology.

We can always ask what values are embodied in our camera (or indeed, in anything at all). But we can also ask how the camera embodies certain beliefs about power. Who has the power, and who is having power exerted over them? In the case of our camera, this isn’t as straightforward as it might immediately seem. Certainly, the people receiving the crowd numbers have power over how they respond to a crowd they feel is too big. And the people who form the too-big crowd might not have many socially- or legally-acceptable choices if they don’t like being asked to disperse. But our camera in particular also shows that there is power in legislation which requires surveillance to be proportionate. Our camera, with its specially-painted pole, shows that the people doing procurement for the municipality recognize the undeniable power of the sea. And our camera, running on a municipally-owned network, shows that the local government is preferring to have power over its own fibre optics, rather than leaving those in the hands of a telecommunications company.

Asking questions about the camera, following the threads we find, and trying to understand this web of relationships gives us access to an understanding of the camera that is no longer limited to superficialities. We begin to understand the story behind the crowd-counting camera that embodies the goal of making the beach safer while respecting privacy.

This is the AI-cology. It’s not revolutionary to say that technologies should be understood from an ecological or relational perspective, but doing so is increasingly necessary. When confronted with a surge of adoption cloaked in opacity and vague terms, and with the language of inevitability, there’s value in finding ways to uncover complexity, look for where the decisions happened, and understand that none of these AI-using systems are ever just objects, just there, or just inevitable.

Further reading:

Jacobs, G., Van Houdt, F., & coons, g. (2024). Studying Surveillance AI-cologies in Public Safety: How AI Is in the World and the World in AI. Surveillance & Society, 22(2), 160-178. https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/surveillance-and-society/article/view/16104