Anatomy of a smart garbage can

Everyday things are collecting and transmitting data. This was one of the promises of the Internet of Things. A humble member of the IoT, the smart garbage can is becoming a ubiquitous street appliance. So what exactly is this thing?

Not everything is obviously big and world-changing. Small, taken-for-granted details have an effect, despite often being ordinary and overlooked. This is why I’m returning to garbage cans today. I’ve previously written about the relationship between garbage cans in public space and the systems around bottle deposits. Now, I want to turn to the garbage cans themselves. It’s time to talk about smart garbage cans and the ecosystems in which they participate.

There are different kinds of smart garbage can on the market and in cities, from different companies, with different approaches and platforms. The two brands I see most frequently are Big Belly and Mr. Fill (other smart garbage cans are available). My goal here isn’t to give an overview of the whole field of smart garbage cans, but instead to draw some attention to something increasingly pervasive that you may not have noticed yet, or might have noticed but not examined. Because I’m not being exhaustive, I’m going to focus on Mr. Fill. It’s more popular with Dutch municipalities than Big Belly, so I’ve both seen it more often and had the chance to casually hear first-hand experiences from people who have implemented it. Aside from that, being made in the Netherlands, Mr. Fill is part of the Dutch smart city development ecosystem. It’s been on my radar for a few years as something that’s getting deployed more and more in the quest to smartify cities and solve the problems smart things are meant to solve.

What is it?

Let’s define terms first. The smart garbage cans being discussed here are compacting garbage cans for use in public or public-private spaces which have the capacity to do some sensing and to provide information over a network. In practice, that means we’re looking at garbage cans that can sense how full they are, can compress the garbage they contain, and can communicate information about things like fullness, battery charge, and locked/unlocked state to relevant people, via notifications or a dashboard.

I’ll make it even more practical: Many municipalities and other organizations with responsibility for a lot of trash have tried to address the problem of over-full garbage cans by bringing in compacting models. With a piece of garbage in your hand, you approach a big, closed, metal bin with a hatch on the front. At the bottom of the bin, there’s a foot pedal. When you step on the foot pedal, the hatch opens out, providing a compartment where you can put your garbage. Releasing the foot pedal results in the reverse – the compartment rotates back in, chucking the garbage into the bin and re-closing the front surface. So far, so mechanical. Chances are good you’ve encountered one or both of these elements before, or potentially both at once. The foot pedal prevents the user from having to touch the garbage can, and the rotating compartment delivers the garbage to the right place without the user needing/being able to reach inside. More importantly, the rotating compartment means that the garbage can is capable of being fully closed, which is important for the compacting part of the design. Let’s say our garbage can is starting to get a bit full. The value proposition of the compacting smart garbage can is its ability to make the waste inside it take up less space. It does that with a great big crunching thing. Which is a very technical way of saying that there’s a mechanism inside the garbage can which lowers down and exerts weight on the waste, pressing it and reducing the space it takes up.

The value of being smart

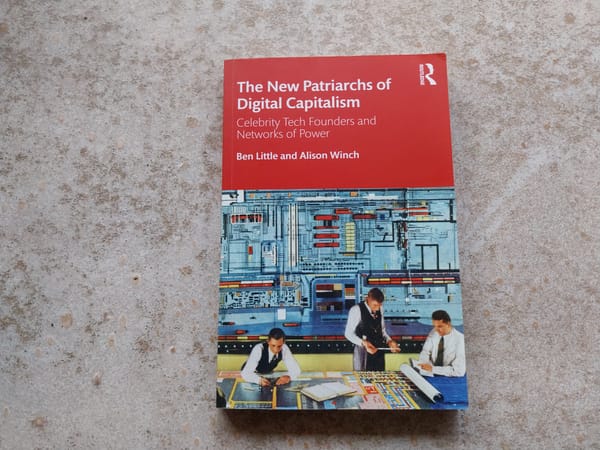

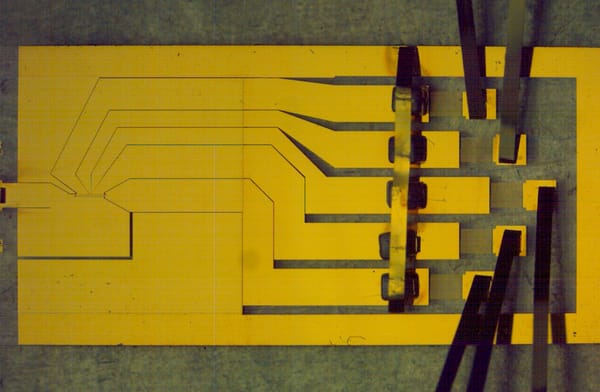

But it doesn't seem to be very smart yet. It’s more Clever Hans than Roomba (if this sentence makes no sense, read my “Stupid smart things” essay). What makes the garbage can meet the qualifications I set out earlier for its smartness? There are two additions to the can that make it smart: a fullness sensor and a wireless network connection. In the case of our Mr. Fill, these are both integrated into a little box that’s mounted inside the garbage can and which they also sell separately to retrofit other garbage cans. It measures the fullness level with a laser, and communicates over a low-energy network commonly used in Internet of Things applications. In practice, this means that each garbage can is frequently transmitting information about fullness to a dashboard which can then be used to plan emptying trips, along with other features like locking garbage cans remotely. If there’s one thing I’ve learned while studying implementations of new technologies in public spaces, it’s that municipalities love a dashboard. In this case, it’s a dashboard that offers the appealing possibility of making a basic but essential service more efficient. The compression means that the garbage can takes longer to fill up, and the fullness sensing means that each can doesn’t need to be manually checked.

This all sounds great so far. It’s the kind of thing we were promised with the Internet of Things. Not only does our garbage can allow improved planning of collection routes, but it does everything in a fairly self-sufficient way. It has a solar panel on its top that provides the minimal energy needed for the compacting, sensing, and communicating. It’s self-contained in that it doesn’t need to be attached into the ground, but simply sits on its own little built-in plate. By all accounts, this is a win for smart city technology. And indeed, I’m not here to do a hit piece on Mr. Fill. For the most part, my aim really is to point at an interesting thing that’s arriving in more and more cities, and to say: Look! That garbage can is online, and it’s got a sensor! This, in and of itself, might be news if you’ve walked past a smart garbage can and not really questioned it.

Smartness and control

But I also wouldn’t be me if I let an explainer just be an explainer. There are a few things about our smart garbage can that have interesting potential implications. First is the potential for increased stratification of labour. Questions around who uses the dashboard, how, and with what power structure are relevant if we’re thinking about the autonomy of the people who eventually have to empty the garbage can. Efficiencies in processes often come at the expense of labour autonomy, and increasing the capabilities of central planners can reduce the planning freedom of workers on the ground. What is the eventual impact of remotely knowing the fullness level of a garbage can and being able to plan with that data, if one of the existing tasks of a garbage collector is to go around, checking the state of the garbage cans? In an enthusiastic video about the use of smart garbage cans at Eindhoven Airport, an employee of the company holding the cleaning contract talks about having more time for other tasks, thanks to the efficiencies of the smart garbage cans. It is, after all, a truth universally acknowledged that a large organization or government in possession of a good workforce, must be in want of an efficiency. Or to be less glib, the quest for efficiency often cuts more than one way, and "more time for other tasks" can sound good in the immediate term, while meaning "need fewer employees" in the long run.

A second itch in the back of my mind when I read documents and watch promotional videos about smart garbage cans is how the product’s features fit into particular narratives around urban safety and cleanliness. The garbage can closes fully, and therefore, prevents animals from getting in and scavenging. This sounds unambiguously good if you want to control your population of rats and gulls. But the method of closing also makes it much harder for bottle collectors to get into the bin, which results in the need for new street furniture like deposit-bottle collection containers (at best, or ignoring the role of bottle collectors at worst). The garbage cans can be remotely locked as well, meaning that closure of waste collection in a particular spot can happen on the fly, depending on other factors. The promotional materials for our Mr. Fill garbage can mention New Year’s Eve as a moment when remote closure might be desirable. This is a nod to the popular Dutch pass-time of celebrating the new year by using fireworks to explode garbage cans. Our smart garbage can has thus been enlisted into a networked effort to pursue a particular public safety agenda.

Finally, there’s the ever-present question of control, or at least the belief in control. I’m kind of snarky about the love of smart city dashboards, which is a little unfair to the dashboards, their developers, and their users. But it’s hard to deny that the more we datafy our cities, the more we’re acting on a belief that with the right data, cities can be better. They can be cleaner, more efficient, less full of rats and exploding garbage. My fear, when decision-makers follow this logic, is that a higher set of hopes are in play than those which can be fulfilled by a cool garbage can.