Civil society and empty bottles

My research methods teacher in grad school had this story about bottle collectors – people who go around town, finding bottles with deposit value, collecting them, and redeeming them. This first part of the story is in Toronto, where beer, wine, and liquor bottles all carry a deposit. In Toronto, if you drink in certain parks (which you're not technically allowed to do, but in the summer, lots of people do it anyway), bottle collectors not only come around and clear away the empties, but they'll often reserve them. They'll come to you, where you're drinking in the grass, and ask you to keep your bottles for them. In the big parks on hot summer nights, there are competing bottle collectors, working the same parks, gathering the empties to take back to the Beer Store for the deposits.

So my research methods teacher in grad school. He had this example for explaining different sectors of society. Government is easy to explain. Ditto the private sector. Civil society takes more doing. Now, you could use the example of voluntary organizations when explaining civil society – groups that are organized around the desire to put their labour into doing something positive for others. There are lots of those, and they’re an easy and obvious example. But he didn't. He used bottle collectors. Bottle collectors, he argued, are an example of an informal kind of civil society doing work which is grafted onto the edges of official structures. They pick up social good where other individuals may let it down. Where someone might be too lazy or drunk or disorganized to save their bottles and take them back for the deposit, thus putting recyclable and reusable materials into the garbage stream, the bottle collector, motivated by the deposit, makes a task of collecting, keeping, and returning the bottles.

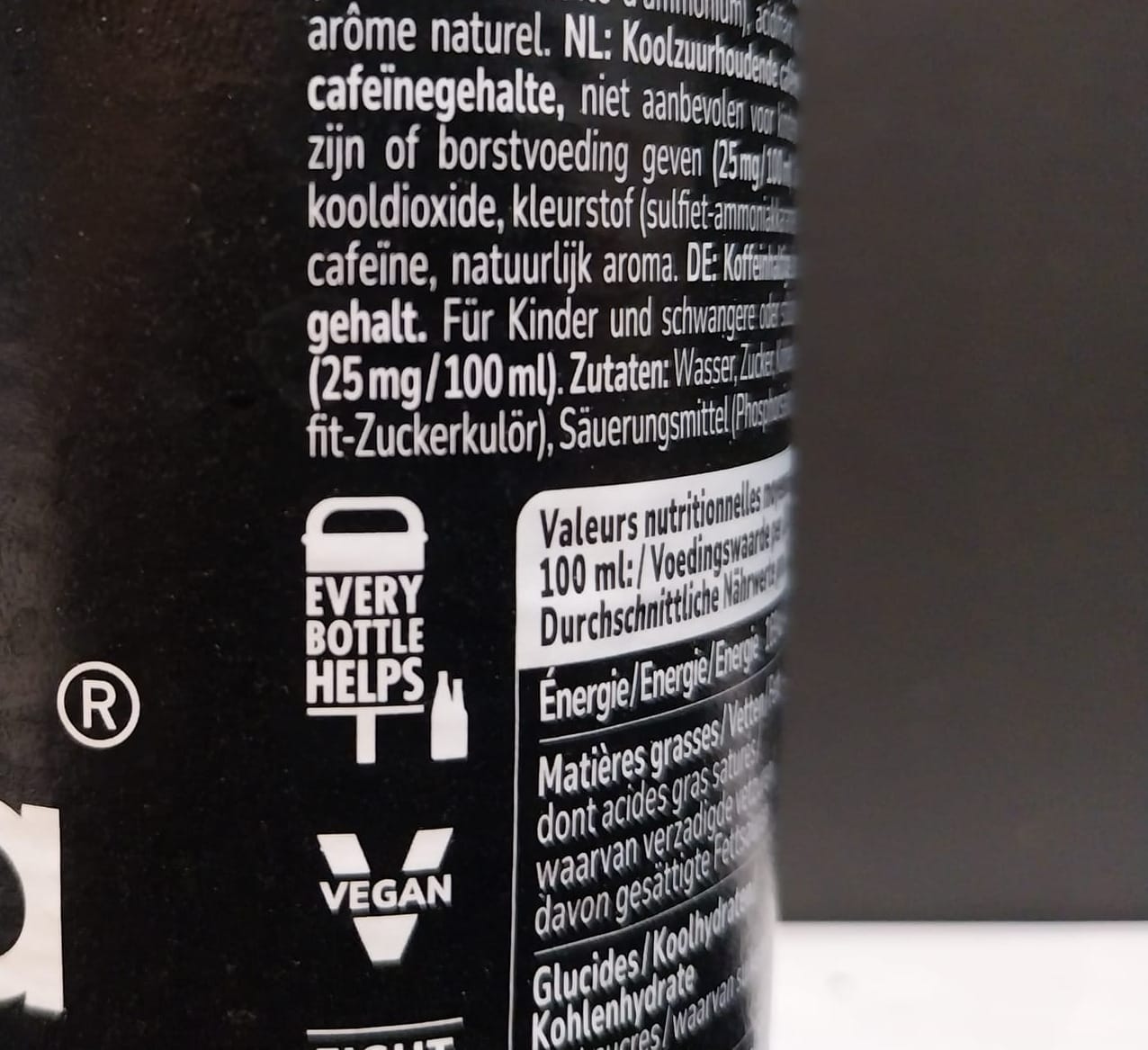

In Toronto, informal practices around supplying bottle collectors were visible not just in the parks, but also on garbage day. On my street, it wasn’t uncommon to see plastic bags full of bottles sitting next to the wheelie bins, sorted out so that they could be easily picked up. But different practices thrive in different cities. I lived in Berlin for a while, where something similar happens. You finish your drink and, instead of putting your bottle in the trash can, you put it next to or under it. If you walk around a busy street on a weekend night, you see little groups of drink bottles clustering under the orange garbage cans which are raised off the ground on poles. Those bottles get collected. They get taken back to the bottle machines in grocery stores and drink shops. They get exchanged for money. One soft drink brand has an icon on its label, showing a raised garbage can with bottles under it, in place of more usual symbols denoting that the bottle has deposit value. This not only demonstrates the existing practice of leaving the bottles out to be collected, but actively encourages it.

The public good of bottle collection

Back to the idea of bottle collectors and their practices as an example of civil society. There’s a public good in making sure the bottles get redeemed for their deposit. If the bottles are redeemed, they have a greater chance of being reused or having their materials reclaimed than if they land inside a garbage can and go to landfill. This public good is acknowledged and encouraged through the assignment of a monetary value for the empty bottle. So far, we’re looking at a system which tends to be some blend of legislation from government, industry umbrella groups overseeing cooperation and logistics, and individual companies implementing their bit, whether they’re manufacturers making sure their packaging is suitable for recovery, or grocery stores installing reverse vending machines to take back bottles. It becomes a civil society issue because the system relies on the cooperation of individuals who buy or consume drinks. When those individuals for some reason don’t redeem their packaging for its return value, in step the bottle collectors.

In the Netherlands, the packaging deposit scheme now encompasses not just glass bottles, but also plastic bottles and aluminum drink cans. A public information advertising campaign has been launched to encourage people to take their packaging back for the deposit, and to carry it along with them if they’re consuming while out and about. Still, bottles and cans end up in municipal garbage cans in public places. On the face of it, this seems like an optimal opportunity for bottle collectors. Unwanted packaging, out in public space, available to be picked up and returned for a deposit. The packaging industry has been set a high goal for recovery of their materials, and the bottle collectors are instrumental in reaching that goal, if the original consumers of drinks aren’t willing or able to return their own containers. The role of bottle collectors in the bottle deposit ecosystem should be a clear win. Government enacts laws and sets quotas, industry tries to implement systems and campaigns in order to meet those quotas, members of the general public participate to varying degrees in achieving the quotas, and where they fail, a specialized sector of civil society, the bottle collectors, steps in, providing a public benefit while also earning money necessary to do things like pay hostel fees or buy food.

The role of government

The elephant in the room, of course, is the relationship between bottle collectors and government. Bottle collectors generally come from a marginalized sector of society, collecting deposit packaging in order to meet basic needs which are not otherwise met. Retrieving bottles from municipal garbage cans in public places is often facilitated by opening the front of the garbage can. The garbage can is often designed to only be opened with the use of a special tool. Unauthorized opening can result in broken garbage cans. Even if the front of the garbage can isn’t opened, looking for cans and bottles can result in the re-distribution of waste onto the street. Municipalities, either by their own initiative, or in response to concerns of other residents, might try to crack down on what they see as a public nuisance. So an arms race could begin between bottle collectors and municipalities, with one group trying to access bottles, and the other group trying to prevent access to the inside of the garbage can. Compacting garbage cans have begun to appear in some Dutch cities, most obviously because they have a higher capacity and their design prevents wind from picking up and blowing away garbage, but with the side effect that their contents are also less accessible to bottle collectors.

Luckily, things seem to be going in a more nuanced direction. Two or so years ago, donation racks began to appear on the sides of garbage cans in some municipalities. The racks are designed to accommodate cans and bottles, allowing them to be conveniently picked up by local bottle collectors. When I first saw one of these donation racks on the side of a garbage can in a neighbouring municipality, I felt frustrated that Rotterdam, where I live, was not doing the same. Now, the other shoe has finally dropped. A new product, the Statiegeldbak (deposit bin), has begun to appear. The design of the bin allows the insertion of deposit cans and bottles at the top, and their removal (no special tool or authorization required) through a small hatch at the bottom. The Statiegeldbak is designed to allow bottle collectors to easily access deposit packaging which is unwanted by its original users.

We now see two systems being implemented on Dutch streets, both with the goal of making it easier and tidier for bottle collectors to access the resource they’re looking for. The installation of these systems, whether the racks or the cans, may initially be a sign that municipalities don’t want bottle collectors opening up garbage cans in order to access packaging, but it secondarily shows that municipalities are willing to accept the role of the bottle collector in the circular economy. At the very least, these systems for sorting deposit packaging away from the main trash stream are an acknowledgement that greater securitization of garbage cans is not succeeding in preventing bottle collectors from doing what they need to do to access their livelihood. But I’ll stick with the more optimistic angle: creating safe and easy methods for accessing bottles and cans shows that municipalities see the role of bottle collectors in society, individuals are willing to make a nominal effort to sort their garbage in public space for the benefit of someone else, and civil society is made up of both the people bothering to sort their garbage, and the people aggregating and cashing in the deposit.

Sources Used

https://www.at5.nl/artikelen/219984/ringen-op-prullenbakken-in-binnenstad-voor-statiegeldflessen