Companion to “The Replacement of geography by standards and what to do about it”

What is the relationship between standards and global flows of movement? This essay explains the replacement of geography by standards, bringing work I did in 2014 up to date, and laying out why you should care.

This week, I’m trying something new. Not new in the world, but new for me, and new for Not so obvious. Previously, I’ve posted essays which explain concepts used in things I’ve written for scholarly outlets (like my essay on AI-cologies). Now, I’m going one level beyond that. What you’re about to read is a synthesis of a whole article, one I published a number of years ago. My purpose today is, first, to give a more accessible version of something that spends a lot of time comparing different concepts and using too many words per sentence. My second purpose here is to try to put the ideas from the article into a bit of context. As with a lot of things I wrote or made many years ago, I find myself surprised and a little disappointed that the phenomenon being described has become a lot more intense than I thought it would be. My explanation of the article, and contextualization of it in the now, bring the arguments I made a decade ago up to date in a much stranger world than the one I was expecting. I’m calling this a companion to the original article, but you don’t have to read the article to get value from this essay.

In 2014, an article called “The Replacement of geography by standards and what to do about it” was published as part of a special journal issue of expanded papers from a conference on interconnections between visual art, performance and technology. I was maybe two thirds of the way through my PhD and was extremely into standards at the time. I continue to love standards, but they’re no longer at the centre of how I conceptualize everything. The article makes an argument I still think is relevant, which is that standards often act like a substitute for proximity, as part of the process of physical objects and human bodies becoming more globalized. I realize that this is already a pretty intense sentence. So let’s break it down.

There are three main components in that sentence: standards are the tools I’m suggesting are being used; what they’re being used for is to replace the need to be near things or people (proximity); and the context of being near or far from things or people is that of an increasing global movement of goods and people. This is going to be the framing I use to explain the article.

Standards

In the article, I spend a lot of time giving different definitions of what “standards” are. After all, the article is premised on the idea that standards are replacing geographies. Out of the varied definitions, I land at a couple traits and functions of standards which I see as important, most particularly that standards are necessary to make the world work as it currently does, in large part by allowing interoperability. Ultimately, I give my own definition of a standard, which is “a set of procedures or rules that renders a practice explicit and transportable.” In talking about the uses of standards, I write that their “function is to allow actors in diverse settings to achieve sameness in their activities.”

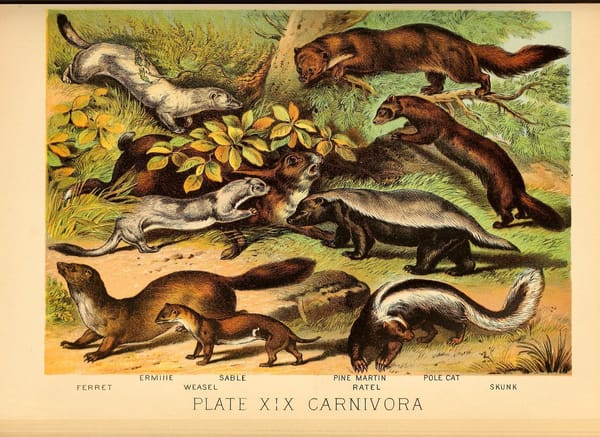

With a basic definition of standards and what they’re for out of the way, the next big task is to relate standards to humans, and to human bodies in particular. This is where two of our concepts blend. To cover the relationship between human bodies and standards, I give a brief history and contextualization of anthropometry, or the scientific measurement of human bodies. Yes, it is just as potentially terrifying as it sounds. Anthropometry has been connected to some horrible and shifty things, like attempts to determine criminality based on face shape (this is physiognomy, a subset of anthropometry), or to define distinctions between groups in colonized countries. But because life is irritatingly complicated, anthropometry is also what allows clothing sizes, growth progress charts for children, and a lot of consistent things in the built environment to exist. In the time since “The replacement of geography by standards” came out, a lot of good work has been done to communicate the problems that come from designing objects and spaces for certain kinds of bodies and not others, and at the root of all of this is the measurement of bodies, and decisions about whose bodies should count.

Proximity and bodies

Proximity and bodies go together because bodies exist in physical places. If we’re talking about the relationship between users and the goods or built environments they’re using, we need to talk not just about what the things are, but who will use them and how. This has been one of the applications of anthropometry. Not in the article we’re currently looking at, but in my book, I look at the history of graded clothing sizes and its relationship to data about human body proportions. Long story short, the wide availability of pre-made consumer goods that have a relation to the human body in some way (whether the size of a shoe or the proportions of a chair) comes down to the existence of data sets about body measurements.

The examples from anthropometry provide fuel for the argument that standards often serve as a replacement for proximity. Not only in relation to human bodies, but in relation to the specificities of things being made, proximity has historically been a feature of manufacturing. Before clear and portable standards, having suppliers nearby was an important step in being able to get compatibility of parts or materials right.

Global movement

One of the better sentences in the article (if I do say so myself) is this one: “The replacement of geography by standards is an attempt to substitute clear, explicit rules and guidelines for local, contingent, cultural norms.” This is the brief, potted, quotable definition of what I mean when I talk about the replacement of geography by standards. And this sentence is how we will now enter into the issue of global movement of people and goods.

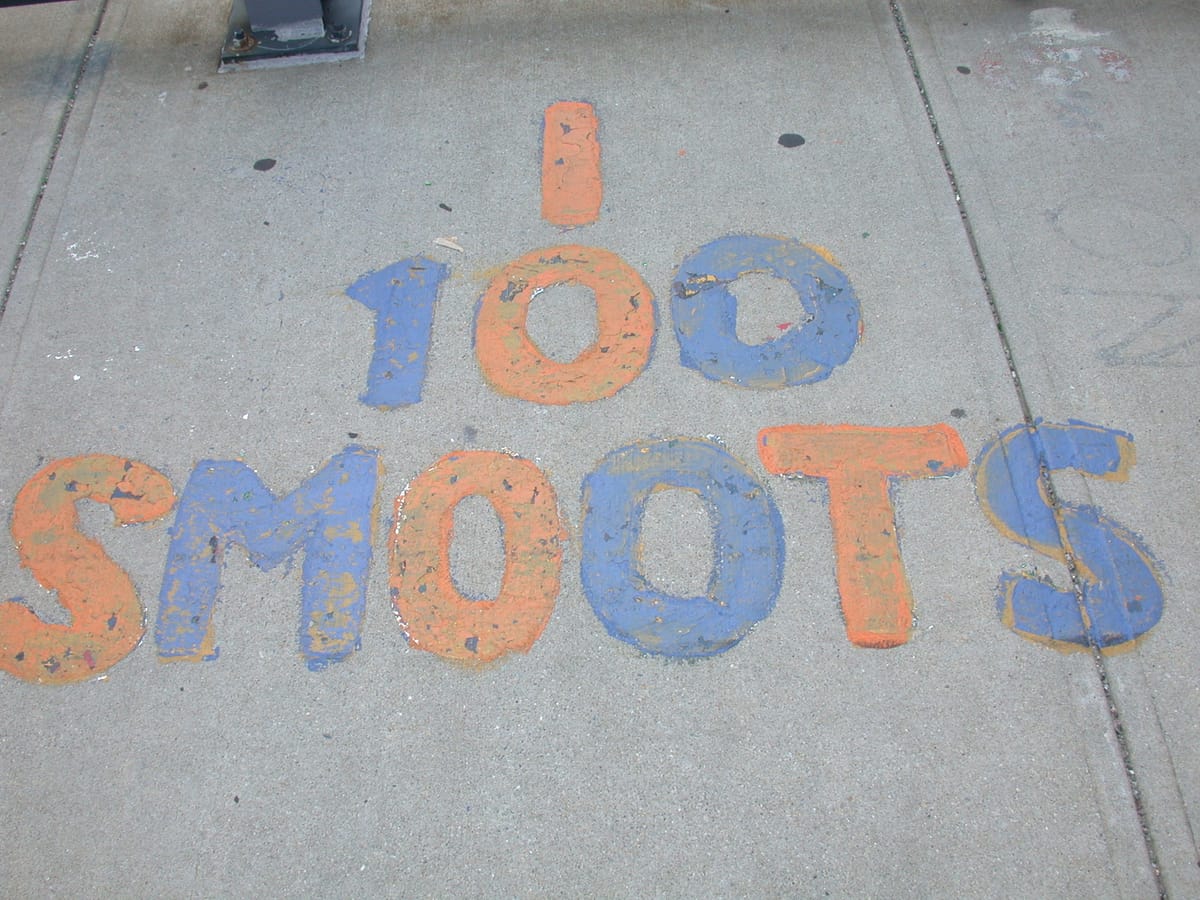

The elephant in the room of all the talk so far about standards is that they are necessary when compatibility or interoperability needs to happen beyond a small group of practitioners who are able to communicate face-to-face with one another. To give a simplest example, if we want to agree on how long a piece of string should be, we either both need to be looking at the piece of string, able to point at and agree where it should be cut, or we need an agreed and unambiguous metaphor with which to compare the string (standards as metaphor are from the excellent work of Lawrence Busch). We need a comparator that’s quite stable and unambiguous, and the un-ambiguity depends on our tolerance for inaccuracy in the string length. We could say that it should be as long as a forearm, but then we need some certainty that the forearms of everyone involved in the discussion are of a relatively similar length, which is a difficult thing to be sure of if we don’t have another, even more stable comparator. Instead of measuring with arbitrary metaphors, we fortunately have access to a global standard (the metre and its larger and smaller associates) which is used almost everywhere, and for which authoritative conversions exist in the places where it isn’t widely used.

All of this is to say that standards facilitate the ability to get things done together, even when we’re not in the same place. They create metrics for comparison, and modes of communication that allow two people, hundreds of kilometres away from each other, to confidently cut a piece of string to the same length as one another, should they so desire. And that’s excellent when it comes to measuring lengths or doing other activities which benefit from unambiguous sameness. It can be less-than-ideal when local variation is desired, or when a global standard comes to replace something that makes a specific place special.

It seems to be broadly taken for granted at this point in time that what I refer to as the replacement of geography by standards is just how things are. I write in the article that this term, the replacement of geography by standards, gives “name to the assumption that physical objects can be the same from place to place, without physical reference or proximity, as long as we can create standards and information systems around those objects.” This may seem basic, but it’s pretty revolutionary, and pretty recent. At its root, this concept is about replacing the mobility of things and people with the mobility of information. While my focus in the article was on objects, and particularly objects that have a direct interface with human bodies (clothing sizes, body scanning, ergonomic decisions), the replacement of geography with at least information, if not actual standards, has accelerated in the last few years.

Yes to interoperability, no to sameness

There’s something I write at the end of the article that’s worth quoting in full:

"As we increasingly replace individual or local geographies with shared standards, negotiating the boundaries between ourselves and our collective (but not always collectively-controlled) rules and routines is of more and more importance."

This matters, because the creation of standards at a distance from the people they may impact can lead to real harm. An awareness that we are living in a moment when high-level standards of various kinds are the water in which we swim is an important first step. Some things can, and ought, to be contested.

Standards, whether they are formal and set by international organizations, or informal and imposed by market-dominant companies, become the substrate for the way things are done. We need to understand that this is the world we are living in, recognize individual and collective benefits and harms, and work to encourage accountability in areas where harms are being done in the name of sameness and interoperability. Replacing the local with the global, or the specific with the interoperable, can be a fine thing, but its fineness is ultimately dependent on the stakes of those it impacts.

And a coda for the academics: If you’ve read this and thought “surely this is just immutable mobiles,” I’ve got your back. The full paper addresses how the replacement of geography by standards relates to other, similar concepts like the immutable mobile.