Digging the internet

In 2014, I made an installation about digital enclosure, bringing visitors into a world of subversive online activism. A group called the True Equalizers were agitating to build new networks, not overseen by the all-powerful internet overlords who controlled the flows of socialization and access.

In 2014, I had the opportunity to make an art installation at Mozilla Festival in London. At the time, I was mostly making projects which could be described as online choose-your-own adventure games about digital rights. The piece for Mozilla Festival was going to be similar, in that it would have an online component played across some websites on a local area network, as well as a social media presence on Twitter. The big departure was that the entry-point to the game/interactive story would be in the festival’s physical space. Previous similar works I’d done just lived online – this one would be a kind of augmented reality (though not in the way we now think of AR), with a flavour of subversion coming from accessing a secret WiFi network running in the building.

The form of the project was fun to work on, with the logo being designed to be easily stitched onto a balaclava, for example, or the enormous banner I made on a bed sheet to install in the space. But what I want to talk about here is the content and premise of the piece.

In When We Awoke to Our Folly, attendees who found the piece via its banner, or through handbills spread throughout the space, would be brought into a world of subversive online activism. A group calling themselves the True Equalizers were agitating to build new networks, not overseen by the all-powerful internet overlords who controlled the flows of socialization and access. Bear in mind, this was 2014 – we weren’t yet living so completely in that dystopia, but the signs were already there.

The manifesto of the True Equalizers went like this:

“WHEN WE FINALLY AWOKE TO OUR FOLLY, IT WAS TOO LATE.

We'd handed over everything to people suffering from exceptionalism. The op-eds called them things like tech bros and technolibertarians. They made the decisions at first because no one else recognized the significance of what they were building. Then, by the time we'd all become dependent on their network, lived our lives inside the systems they'd built, they were the only ones who could understand the decisions they were making. That was what led to their exceptionalism. They believed themselves better — or at least more powerful, which was often true — than everyone else. They were the ones who understood, while we were all sleepwalkers, dozily using the products of their invention.

We're waking up now, all of us. Some people call our movement the True Equalizers, because we want just that: we want to see everyone equal in the eyes of the network, no one subordinate to anyone else, no one trapped or bought or sold or walled into an enclosure of someone else's making. We're waking up and freeing ourselves, making the network our own.”

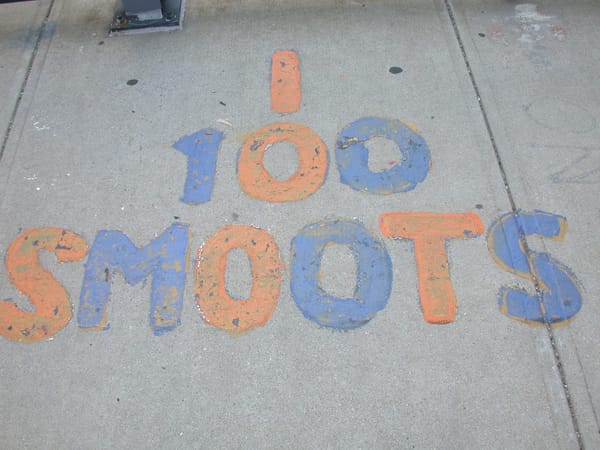

Now, here’s the fun part. The principles of the True Equalizers, and their struggle, were a translation of a real movement, the Diggers, originally known as the True Levellers. The Diggers were a socialist movement in England in the middle of the 17th century, fighting back against the enclosure of common land and the dispossession of peasants in favour of land owners. The Diggers originally called themselves the True Levellers, in contrast to another group, the Levellers, who were also active at the time. One of the points made by the Diggers was that the Levellers weren't thinking big enough, wanting modest changes to the social order, compared to what the Diggers were after.

While briefly summarizing the enclosures is difficult, for my purposes here, this was a series of actions resulting in land which was previously in common use being consolidated or enclosed for the exclusive use of property owners. The key point is that the Diggers were one of many groups opposing the enclosures and, in their case, working towards the creation of agrarian communities with a foundational belief in equality of all people.

Digital enclosures

The idea of the enclosure of the digital commons is one that has been popular for a couple of decades already. In making When We Awoke to Our Folly, my key source for understanding the Internet as a commons was the work of Lawrence Lessig. He’s been a major influence in the development of the concept of a digital commons, deploying the metaphor of digital and intellectual property resources which were not just to be used for the profit of the few, but for the benefit of society.

Smashing together the digital commons and the ideas of the Diggers, I came to three concepts I wanted to port from the history of land enclosures to a speculative and dystopian world of digital enclosure:

1. A small elite are dividing up the commons and impeding the ability of the majority to live full lives without the fear of oppression from those in power.

2. A number of responses to those enclosures are arising, some of which have to do with trying to claw back a modicum of power. In the case of the historical enclosures, one of the things the Levellers wanted was voting rights for male heads of household – this would be a modest improvement in representation. This was not going far enough, in the eyes of the Diggers. They viewed voting rights as a necessary change, but not necessarily enough to stop the trend of land loss. Imagine it being parallel to an ethics advisory board formed by a big tech company, but never listened to, while the company continues to act against the interests of users.

3. So, a smaller group of more radical fighters-against-enclosures respond to those enclosures by trying to tear them down, and by enacting a sort of radical sharing, getting the masses back onto the land, getting them farming common land, getting them living communally.

The True Equalizers in my narrative were the digital equivalent of the more radical groups exemplified by the Diggers/True Levellers. They were determined to squat the enclosed spaces and build a new, more equal society on top of the land that they believed had been unjustly taken from them.

Life moves fast

Looking back at this work now, a little over a decade later, the modesty of the project blows my mind, as do the differences between physical space and digital space. First, the modesty. In 2014, I pitched the story into what I thought was a radical enough future to get people thinking about how awful it would be if something so extreme happened. Eleven years later, it’s so much worse than I’d imagined. Most platforms are walled gardens, everything is scraped and monetized, and behaviour of users is manipulated and exploited. Escaping the walled gardens of social media platforms feels like an impossibility for many people, as their social lives or livelihoods can depend on their use of a particular platform. We have indeed sleep-walked into the products of the architects of these systems, and their exceptionalism is so much worse than I feared.

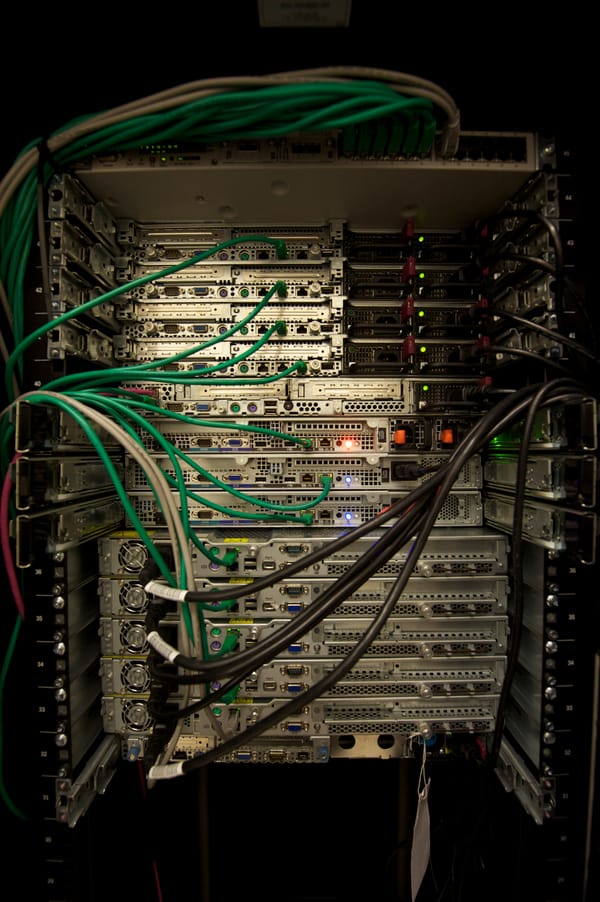

More importantly, there’s a difference between digital space and physical space which I hadn’t fully seen when I wrote the story of the True Equalizers. When the Diggers decided to plant vegetables on common land, that land existed. Whether it was under threat of enclosure or not, there was the objective reality of dirt – and the dirt was there in the same form both before and after the land was enclosed. When we think of the digital commons, we mostly need to bring the land ourselves, too. The platforms built by corporations may rely on public or shared infrastructure and open internet standards, but though they may be built on top of public goods, the platforms themselves are already private goods, right from the start. Efforts to build commons on top of these private platforms may succeed in some degree, but they’re ultimately at the mercy of the platform owners. We've seen this with social movements and communities which are built on top of commercial platforms and then suffer when policies change. So the difference between the Diggers and those who want to create more equal worlds in digital spaces is that on the internet, we need to bring our own dirt to dig. There have been some very hopeful developments in that direction, with things like federated social networks demonstrating that it’s possible to start with more equal and collective structures from the beginning. Looking back at my vision of the True Equalizers, I see it as more important than ever that we bring our own dirt and start digging.