Interview with the seagull

What does it mean to think about the planet’s inhabitants, beyond the humans? Is thinking about them enough, or do we need to find ways to consult them?

Here’s the set-up: many people now agree that humans need to think about the other inhabitants of the planet we share. Among environmental scientists, this is pretty much a given. In social science circles made up of critical scholars, this is generally accepted. In policy and government circles in many European countries, people are fairly on-board, as long as being good for the planet is also good for the economy.

But what does it mean to think about the planet’s inhabitants, beyond the humans? Is thinking about them enough, or do we need to find ways to consult them? There’s a growing body of scholarship on the more-than-human. One way of thinking about more-than-human research is that it is about taking the lives of nonhumans “seriously and to thus step away from the modernist dismissal of nature and nonhumans as anything but resources” (Bastian et al, 2017, p.2). This is a powerful and radical departure from some of the more usual ways of thinking about nonhumans.

Nature as resource

More often, nonhumans are thought of as resources, as solutions, as things which can be deployed to fix human problems. Ecosystem services, a concept which considers the value provided to humans by nature, is one popular way of thinking about the relationship between the human “us” and the “everything else” of all the constituent members of ecosystems. Ecosystem services is only one example of the way Earth’s other inhabitants get viewed as resources, and even a comparatively positive example of the genre. After all, the dominant way of thinking about nature is that it exists as a resource for humans to use to their benefit, regardless of the outcome.

The idea of nature as a resource, or as something that needs to be cared for so that humans can thrive, is the starting point for a radical change in direction. If we begin to think about the more-than-human inhabitants of Earth as entities in their own right, we need to think of them not as resources for our use or providers of services, but as stakeholders with their own needs and positions. This flips the usual logic on its head. Instead of thinking about nature (a big and abstract term) as a resource and humans as its users, what does it mean to consider the position of a more-than-human entity?

The participant gull

This is where the seagull comes in. Writing and thinking about more-than-human entities as stakeholders in projects – on a level with human and organizational stakeholders, deserving of a seat at the table – the question of participation comes up. Others have done excellent work on the question of how to think about and do participation with more-than-humans (see, for example, Bastian et al in the reference list below), but it’s early days and there are no well-established or monolithic ways of doing this work. That’s all to the good, and I hope we don’t end up with monolithic and dogmatic methods, because that would go against the important principle of meeting participants where they are and taking context into account.

But the seagull (with apologies to the ornithologists screaming that the existence of the seagull is only as a customary and colloquial category, not as any actual or specific type of bird). The seagull, for me, is an example of low-hanging fruit. Many of us live with them in our cities. They’ve performed an amazing feat of adaptation to become urban scavengers, as humans have taken over or depleted their previous food sources. We humans find them irritating when they steal our fries or ice creams, or dig in our garbage. But we are residents of the same places, interacting with each other, for better and for worse.

The gull survey

For better and for worse, but who gets the better and who gets the worse? This is one of the big questions if we look at the relationship between people and gulls in cities. In Europe, many gulls are classified as protected species. This means that disturbing their eggs and moving their nests is not allowed. But gulls have begun to nest in cities, and their presence and behaviour are being reported as nuisance by their human neighbours. In Rotterdam, this has resulted in a study by the municipality into gull nuisance experienced by human residents. The goal of the study? Collect evidence to support an application for an exemption, to be allowed to carry out nest management activities.

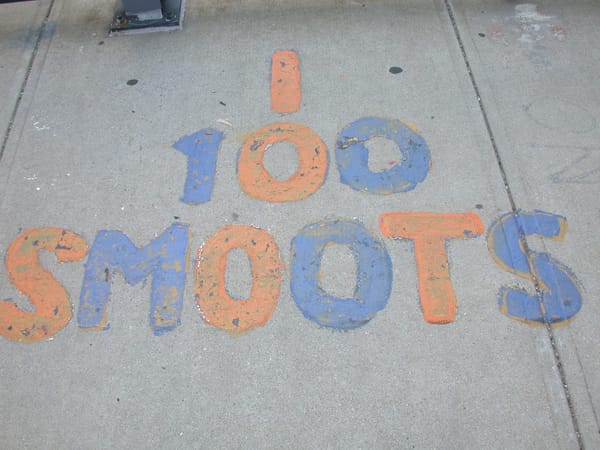

Evidence was collected from residents in three neighbourhoods, over the course of two years. Residents being surveyed used a mobile phone app which exists to collect feedback on various surveys developed by the municipality. The surveys in this case covered questions about what kind of nuisance residents were experiencing from gulls (noise, fouling, garbage, attacks), with what kind of frequency, and with what impact on the well-being of the respondents.

Mostly, the complaints were about noise, poo, and garbage. Gulls were loud, gulls made it less pleasant to eat in one’s yard or on one’s balcony, gulls pooped on cars. What’s interesting to me isn’t really this outcome, but what went into getting it. The mechanism for collecting the information was the app I mentioned before, the one that delivers surveys to residents. People who want to have a say in what the municipality does can have a chance to weigh in on things by answering those surveys. Because of the responses given on the seagull surveys, we know what roughly 150 people in Rotterdam think about nuisance behaviour from seagulls.

Survey the gull?

How do the gulls get to respond? The short answer is, they don’t. They’re not participants in this discussion, they’re instead a problem other people are talking about. The end goal is to reduce nuisance experienced by humans from seagulls.

What if we did think about what the seagulls want? What if the seagulls were allowed and able to comment on nuisance behaviour from humans? Is there a meaningful way to consult the gulls about their preferences, and would producing meaning for humans also produce meaning for gulls? In short: what would it mean to interview a seagull, or give a seagull a survey? Through the survey delivery app used by the municipality, (some) human residents are able to share their opinions, shoring up the local government’s argument that it should be allowed to, in this case, conduct nest management on the gulls. What would that survey app be for a gull?

It may seem a little zany to want to interview the seagulls. After all, the local government is (in the current best-case) meant to govern for the benefit of its human residents. If the human residents are bothered by gulls, who cares what the gulls want? This follows the logic of seeing more-than-humans as less important than humans, less worthy of a voice than humans. We’ve built cities which are incentivizing gulls to make their nests on roofs, but we’re frustrated by gulls living their lives among us, communicating with each other, having basic bodily functions, and looking for food. We’re giving some mixed signals, building a handy habitat and then being angry when they use it.

While I’m not sure how we’d go about interviewing a seagull, giving it a survey, or inviting it to a focus group, I am sure that it’s worth thinking about how to include the voice of the gull. Whether or not there are ways to do research on gull preferences which gulls find relevant, humans could certainly benefit from beginning to think about how our co-habitation feels for the more-than-humans we share our cities with.

References

Bastian, M., Jones, O., Moore, N., & Roe, E. (Eds.). (2017). Participatory research in more-than-human worlds (Vol. 67). London: Routledge.

Reid, W. V., Mooney, H. A., Cropper, A., Capistrano, D., Carpenter, S. R., Chopra, K., ... & Zurek, M. B. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being-Synthesis: A report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Island Press.