Stupid smart things

Automation does not, by its nature, need to be bad. Can we disentangle ourselves from automation that disrespects user rights and makes heavy use of computation? I make the argument for the importance and value of "stupid smart things."

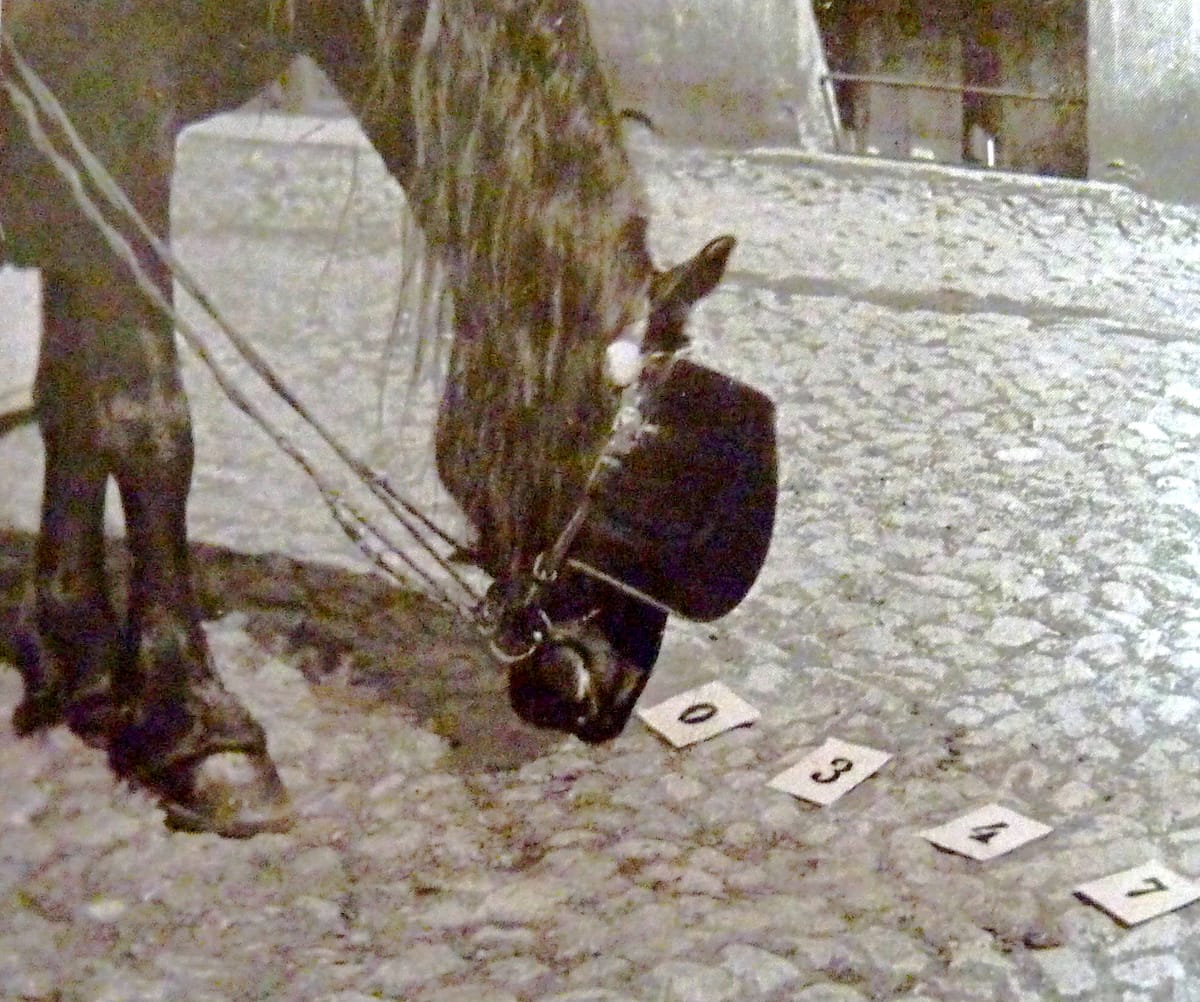

In 2016 or 2017, I bought a robot vacuum cleaner. It was very cheap for the time, and was endearingly stupid compared to other robot vacuums on the market. In fact, I bought it for the traits that made it stupid. I later named the vacuum cleaner Hans, after Clever Hans, a horse who could allegedly count and do math. It was eventually discovered that Clever Hans was not doing math, but was instead observing the unconscious reactions of his trainer. Hans was not a math prodigy, but an empath. This is why I named the vacuum cleaner Hans: it was executing a task which appears to require one kind of intelligence, through other means.

Hans the vacuum cleaner did not do many of the things higher-end models could do, and was not "smart" in the conventional way of robot vacuums. Hans did not make a map of my apartment, it did not have any functions which allowed it to detect walls before bumping into them, and it did not have the capacity to connect to the internet. Instead, Hans the vacuum cleaner operated algorithmically: it carried out a series of actions in sequence, and with a simple set of conditional loops. When starting its routine, it would drive forward for a set period of time and, if it failed to bump into anything during its forward movement, it would then begin one of two possible patterns for moving around the room. If it bumped into something, it would execute a small turn, move forward again, and then either bump into a new obstruction or succeed in moving forward. Repeat until the time period of the chosen program is over.

Hans the robot vacuum cleaner was a “smart” object in the sense that it represented an additional level of automation beyond the norm of a vacuum cleaner, included slightly more complex computation than what might be found in a conventional vacuum, and could act somewhat autonomously. But it wasn’t smart if networking capability is considered a precondition for smartness. Hans did not transmit information to any other device, and did not create a data trail on any server. Hans did not “learn” or adapt over time to the layout of my home, a user-defined cordon, or any other factor that differentiated cleaning my floor from cleaning some other floor. Hans was not a member of the Internet of Things.

Instead, Hans was pre-programmed with a set of actions which allowed it to react to certain kinds of complexity common in its environment and allocated task: in short, Hans could vacuum most floors through a process of trial and error. Hans was “smart” in comparison to the average vacuum cleaner, but not in comparison to higher-end robot vacuums.

Hans was what I like to think of as a stupid smart thing. Hans automated a task through the addition of a technology which was not the standard in performing the task, and did not require network connectivity to do so. To my mind, the kind of automation offered by stupid smart things is the best kind of automation – it makes tasks easier or executes them better, but without adding permanent dependence on external parties, and without consuming drastically more resources. In service of this argument, it’s worth rolling back for a moment to think about the nature and role of automation.

Automation doesn't need to be bad

There are all kinds of different ways of achieving automation, and all kinds of reasons for wanting to automate tasks. Some automation is robots taking our jobs, and some automation is a dishwasher (which is also a robot taking a job, just further back in history). Not all automation is bad, and some of it is extremely helpful. My belief is that we should aim to prioritize automation which makes tasks easier, which does not directly conflict with human rights, and which is not aiming to minimize the power of individuals to live with dignity and independence. Rights-respecting automation is automation which makes jobs safer, but maintains the value of the worker. In the home, valuable forms of automation work towards the goal of having a good standard of life with more time and energy to do the things that make life worthwhile, while respecting the privacy and basic rights of users. In short, automation can and should help people.

The kind of automation I find most problematic is the version that sucks up big piles of data in order to work. We’re seeing some versions of that now, with the AI boom, where the automation that is taking place (say, suggesting the next word in the email you’re drafting) tends to rely on the wholesale consumption and processing of available data, including, for example, the contents of your and everyone else’s emails. This is automation which is also, in the terminology of social psychologist/labour scholar Shoshana Zuboff, informated. That is to say, it's automation which creates and collects data during the process of carrying out the task.

The problem with data-slurping automation

For me, there are two issues in this kind of automation. First, it often comes in a form which does not adequately respect privacy and individual rights. There are some good, older examples of risks associated with the cavalier use of data scraping and analytics. A classic comes from a 2012 New York Times article about how major US retailer Target sent tailored promotions to customers who it deemed to be pregnant based on their data trails. Proactively offering tailored promotions may seem like a nice idea when dreamed up by a marketing team, but it’s less nice for customers who haven’t yet told their families of their pregnancies. That one took place before the current AI hype, but is enjoying a bit of a renaissance as a case study right now thanks to the popularity of predictive analytics. If we’re to take for granted that current methods of data analysis are better than they were in 2012 (or at least that they have access to more data), all kinds of abuses (which seem like a good idea to someone) are possible in our current data usage landscape. The not-very-cute story about having one’s pregnancy leaked is only the tip of the iceberg when the tasks we do, products we use, and technologies we let into our jobs, lives, and homes are all creating massive stores of data through what appears on the surface to be simple and straightforward use.

The second problem with automation which has data collection and analysis built into it is resource usage. I probably don’t need to belabour this one too much, as the environmental impact of AI is one of the major arguments we’re currently seeing against fast and massive adoption of AI-driven tools. I hope it’s not too controversial to say that if a basic task can be achieved without requiring additional computation, and without needing to communicate with a data centre, then the parsimonious option is generally going to be more environmentally-friendly. While there may be specific exceptions to this rule, I hope we can at least agree that being served advertisements by the screen on your refrigerator, for example, is a pretty unnecessary use of computational power and storage. While anything with ads is easy to pick on, I live in the hope that we can extrapolate scepticism of that sort of use to applications like asking Alexa to play a song, or having your vacuum cleaner create an up-to-date map of obstacles in your house. While these last two applications might provide some use value, it may be about time to start asking ourselves whether those small conveniences are worth the trade-offs, both environmental and otherwise.

Good automation

If a lack of respect for user rights (and we’re talking rights in principle and spirit, not just respecting applicable laws) and an excess of resource use make automation bad, does that mean that the opposite results in good automation? It’s a start, at least. Automation which minimizes data creation, for example, is already on the right track for being more privacy-respecting (thus, protecting a basic right) and for minimizing the need to transmit information and do computational tasks elsewhere (more minimal use of resources). I return to the example of Hans the vacuum cleaner. In order to determine the location of a wall or other obstruction, Hans needed to run into it. With a soft front-bumper, the “run into it” method of way-finding was effective enough to locate and navigate obstructions. Hans did not need to collect or transmit any information in order to use this method.

On the flip side, the addition of a camera and an internet connection to a robot vaccuum makes it infinitely more likely to expose personal images. There’s been at least one case of images taken by Roomba vaccuums being subsequently leaked. While that incident involved a device that was in-development and was not available on the consumer market, it’s one small corner of a far larger issue: much of the automation which is coming out of the current AI boom is explicitly about data collection and analysis. The devices and services we use are often designed with the intent of collecting and transmitting information, which is subsequently used for the further development of resource-intensive, data-hungry systems. It’s a perpetual motion machine of resource-hungry, rights-disrespecting automation.

What gets lost in current discussions of automation is that not all automation needs to be bad. Not all automation requires the collection of data and training of machine learning models by a combination of worker exploitation and user rights disrespect. Not all automation requires a data centre. Not all automation will take your job and replace it with a worse one. The Luddites didn’t hate power looms, they hated worker exploitation. Automation is not intrinsically bad, but it can be done very badly indeed. The narrative that the kind of technical progress we’re currently experiencing is the only kind available is a narrative that disregards the kinds of automation that can make life a little nicer, a little easier, and a little less effortful. A stupid smart vacuum cleaner like Hans might have an efficiency disadvantage when compared to a vacuum with a map of your house and all its contents, but is the difference so big that it matters? Give me the stupid smart things, the things that automate tasks I dislike without shuffling my data off to someone else’s computer. Give me the stupid smart things that do the job pretty well, and make no pretences of learning. Give me the kind of automation that automates without informating, does the task at hand, and nothing more.

Further reading

On the concept of informating:

Zuboff, S. (2015). Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of information technology, 30(1), 75-89. Available from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1057/jit.2015.5