At The Hare

This week, I'm breaking from the norm. Instead of an essay, a piece of short fiction about exoskeletons, logistics centres, and darts. It's called "At The Hare."

It's a bit of a departure this week, in honour of Winter Silly Season. Instead of an essay about some aspect of society, technology, or any of the other things I normally write about, today is a short story. Also about the impacts of technology on society. I wrote it just after I moved from England to the Netherlands, and still had places like Portishead (pictured in the photo above) on my mind. It's called "At The Hare" and in a nod to Christmas, it's about semi-automated fulfilment centres. Next week will also be frivolous, and the normal substance will resume in January.

At The Hare

“If you wear the haptics all day, you get worse at darts. It’s as simple as that. They still try, the dears, but it’s not how it used to be. Like a phantom vibration from a mobile phone – even when you’re not wearing the haptics, you feel them.”

“Do you get used to the buzzing?”

“I wouldn’t know,” she says, “I haven’t worked in the fulfilment centre. They’re not very good jobs. But they’re jobs. The village needed jobs.”

She turns away to serve a patron. The place is more of a Samuel Smith than a Wetherspoon. Of course, it’s neither. It’s hers. Her rules, her dartboard, her beer prices, her subscription to the satellite sport channels.

“Yes dear, what can I get you? Pint of bitter? 4£.”

Kind. Efficient.

“Anyway. The centre. I have this place, so I didn’t need to look for work there. You can ship beer, but you can’t pack up a social life in a little mailer. As long as people keep coming here, I’ll be fine. Wouldn’t mind having one of those hoppers some days, though.”

“Hopppers?”

“Exoskeletons, they’re called. But who has time to say that?”

“Engineers, I guess…?” I shrug, and realize too late that it was a rhetorical question.

“From what I hear, the hoppers sound handy. Lift more, reach higher, don’t get tired so fast. Wouldn’t mind having one of them for doing the kegs. Then again, you take it off at the end of the day and you’re just an old man again. So this is probably better.”

She laughs, as if an old man is the last thing she’d want to be.

“Tell me more about the darts.”

“John, over there – don’t look so obvious! John’s been very down since he started at the centre. Four years running, he won the tournament. We’re not having one this year. Too cruel.”

“Is it just the darts? I mean, do they feel it all the time?”

“Anything delicate, really. In a way, the new pint was a blessing. A little less beer in the same glass makes it a bit easier. The shakes don’t go so well with a full glass.”

“I suppose the new pint is good for you, too. For business?”

Daggers. Absolute daggers, she’s staring at me.

“No. The kegs cost more than they used to.” Then, slowly, like I haven’t the remotest idea how life works, “That was the point of the whole thing. If the beer is going to cost more, you change the size of the pint, not the price of the drink. Prevents a consumer panic. Like those Toblerones.”

She explains it like it was the only thing that could have happened. As if the new pint was a foregone conclusion. At least it’s good for something, if it saves the carpet from the side-effects of the haptics.

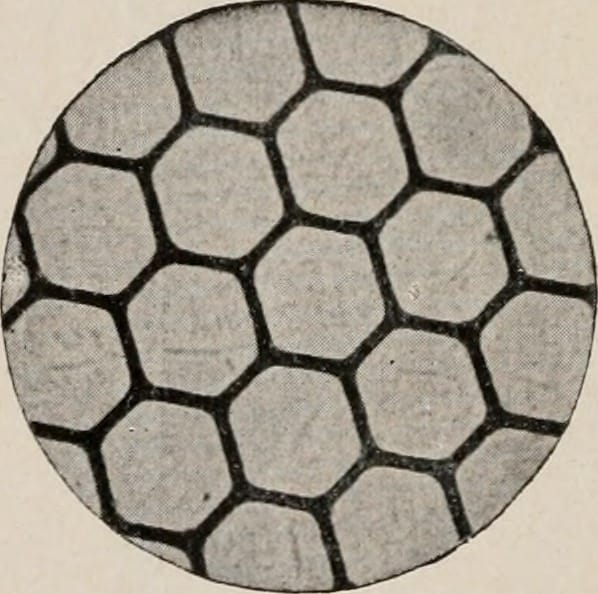

The haptics, or “geo-haptic feedback gloves” as the patent calls them, do roughly what their name implies. They provide haptic feedback – a gentle vibration – based on which box or shelf you’re meant to reach into. And they make you worse at darts, apparently.

I look around the room and see the amazing human ability to adapt. The pub is packed with men who should be pensioners, who should be spending their time watching daytime quiz shows on TV, digging their allotments, coming to the pub with a newspaper and holding down a table all day. Instead, they go to work every day, climb into exoskeletons that give them superhuman powers, and use those powers to meet quotas for putting items into boxes.

“How do I get there?”

Again, she looks at me like I’ve asked what colour the sky is.

“It’s west, as you leave the village. Next to the motorway.”

I finish my drink, a little faster than normal.

“One more thing. Almost forgot to ask. Do you get your orders any quicker, being so close to the fulfilment centre?”

Flat: “No.”

I leave The Hare, down the high street, to the edge of the village. From there, it’s either the motorway or cross-country through the fields.

After ten minutes walking, looking for the fulfilment centre, I realize I’ve been seeing it all this time. The camouflage, which sounded ridiculous when I read about it, works better than I could have imagined.

The bands of blue and green decorating the building blend into the sky and scenery. But it’s the size that does the most to hide it. It goes on so far to either side that, even at a distance it becomes the terrain. The blue bands don’t just match the sky, they are the sky now. It’s not until I get close enough to see the details that I really notice the difference between building and landscape. A door finally breaks the illusion of the artificial horizon. From the top of a small rise, I can finally see the fences, the parking lots, the differences between the building and its surroundings.

The utter, utter arrogance of the whole thing finally hits me. The outside of the building does just what the inside does. It bends reality with its size and influence. It hides against the sky, pretending it’s always been there. It takes the resources around it – the people, the land, the convenient placement at the junction of two major motorways – and weaves them into its own ecosystem.

From the vantage of the pub, it seemed like a story, distant, a choice. From here, I realize what everyone else sees already. It’s all there is now.

I smooth the creases in my CV. Good thing I don’t like darts.